BIMSTEC and Security Cooperation in the Bay of Bengal

Founded in 1997, with the Bangkok declaration, BIMSTEC’s name reflects its original mission. First, this initial group of states was meant to be geographically focused on the Bay of Bengal (B) with an initial cluster of five littoral states (India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand and Sri Lanka). Second, it was conceived as a “sub-regional” initiative (I), connecting South and Southeast Asia, rather than a formal, inter-governmental, regional organisation. Third, and most importantly, its focus was conceived to be multi-sectoral (MS) with an emphasis on technical and economic cooperation (TEC).

Yet this original, flexible, sub-regional, technocratic and economic dimension of BIMSTEC, including an ambitious FTA that dragged on since 2004, has gradually withered away. For the last two decades, BIMSTEC has gone through various phases of expansion and reinvention. In 2004, the two landlocked Himalayan states of Nepal and Bhutan joined, giving the organisation an inland dimension. Many new sectors were added subsequently, bringing the total areas of cooperation to 14. This diluted the foundational focus on trade and economic integration. Finally, BIMSTEC also assumed a heavier, more formal profile, including a new secretariat in Dhaka (2014) and a charter giving it legal standing (2024).

Yet the most notable shift for BIMSTEC has been its growing focus on security cooperation, particularly since 2016, following the leaders’ retreat that India hosted in Goa. Since then, over the last eight years, there has been an expansion and deepening of security-related matters, including on intelligence and counter-terrorism, as well as a new security approach to energy, health and food. Four meetings have been held of the BIMSTEC “national security chiefs”. And a variety of official and track 1.5 dialogues have been established on security cooperation.

The late securitisation of BIMSTEC was however a rather unusual development given that regional organisations in South and Southeast Asia have traditionally either refrained from engaging in security cooperation, as in the case of SAARC, or taken several decades to build the requisite trust to do so, with far more robust institutions or under the umbrella of external powers such as China and the United States, as in the case of ASEAN.

Why has security cooperation been gaining ground within BIMSTEC over the last few years? There are several possible explanations. First, India’s attempt to add a security dimension to its Act East policy following geopolitical competition with China in the Bay of Bengal, for example on sea lines of communication. Second, while smaller member-states are increasingly keen to engage India as a regional security actor they may be more comfortable with a multilateral platform such as BIMSTEC than bilateral cooperation which carries the risks of politicisation and domestic opposition.

Finally, in what remains one of the least integrated and most conflictual regions of the world, member-states may also be more cognisant of how security cooperation is paramount to enhance political stability, institutional resilience and economic development.

Finally, in what remains one of the least integrated and most conflictual regions of the world, member-states may also be more cognisant of how security cooperation is paramount to enhance political stability, institutional resilience and economic development. The securitisation of BIMSTEC, beginning in 2016, coincided with one of the most peaceful periods of the region.

While we examine these possible causes in a longer study, as part of the Sambandh Initiative for Regional Connectivity at CSEP’s Foreign Policy and Security vertical, in this piece we focus on two separate tasks based on a survey of open-access sources. First, we empirically map the trend of how BIMSTEC has expanded its sectoral cooperation to both traditional and non-traditional security cooperation, from counter-terrorism to energy and food. And second, we discuss the possible consequences of BIMSTEC’s securitisation, including the major challenges for the seven member states to sustain and deepen security cooperation in the Bay of Bengal region.

Mapping the Shift Towards Security under BIMSTEC

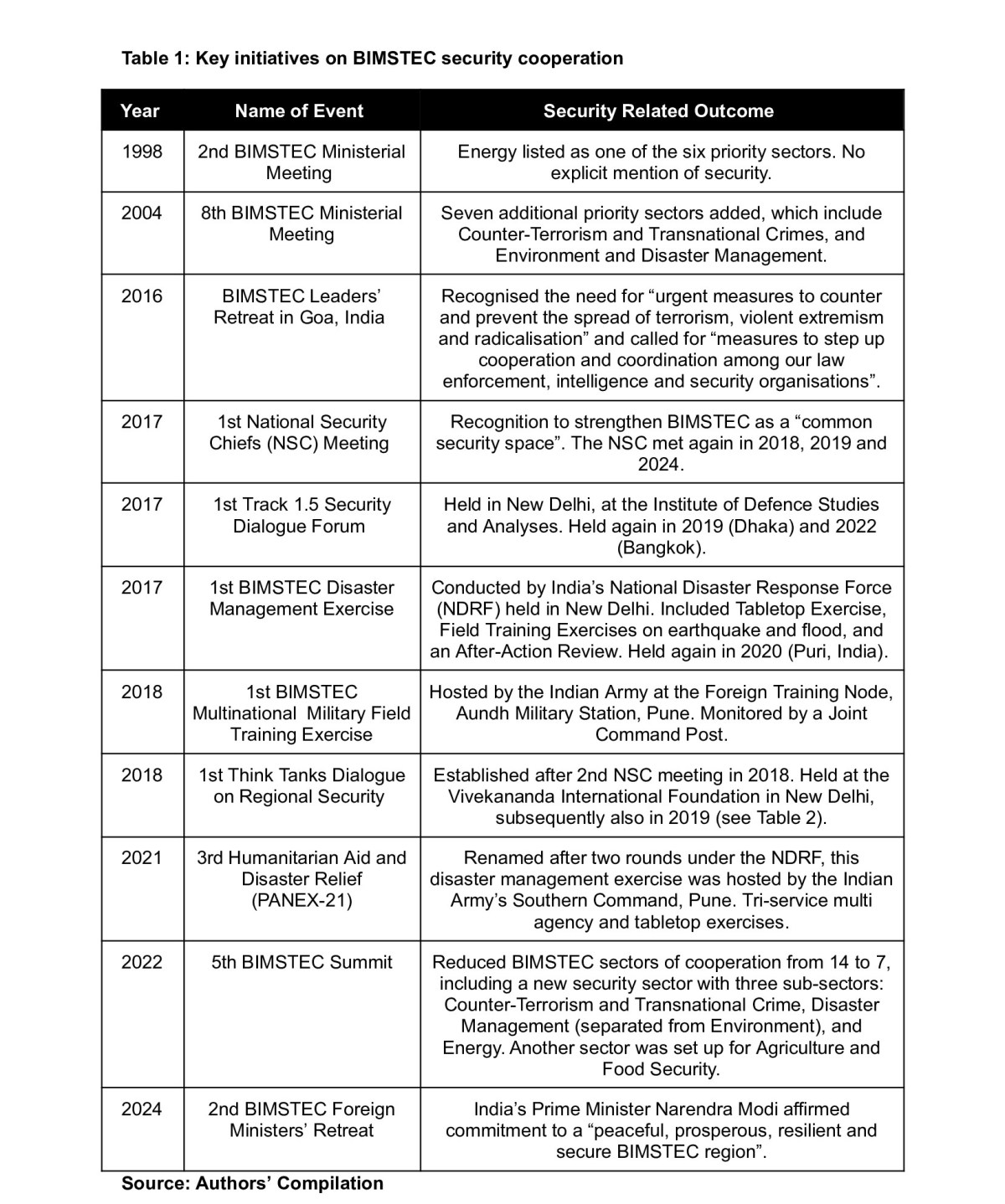

Following the 2nd BIMSTEC Ministerial Meeting in 1998, the organisation identified a set of six priority sectors for cooperation. However, none of these sectors were directly related to security. In 2004, following discussion at the 8th BIMSTEC Ministerial Meeting, these sectors of cooperation were expanded to 14, with Counter-Terrorism and Transnational Crime being one of the seven additional sectors. However, there was still no specific sector for security-based cooperation.

The 2016 BIMSTEC leaders’ retreat, hosted by India at Goa, marked a turning point: for the first time, member states committed to formalising cooperation between their intelligence and security organisations.

The 2016 BIMSTEC leaders’ retreat, hosted by India at Goa, marked a turning point: for the first time, member states committed to formalising cooperation between their intelligence and security organisations. The following year was marked by the first meeting between National Security Chiefs from the seven member states, who referred to the Bay of Bengal as a “common security space”. Later that year, a Track 1.5 Security dialogue forum would also be held in India, addressing both traditional and non-traditional security. And in 2018, New Delhi also hosted the first BIMSTEC Think Tanks Dialogue on Regional Security.

The tides were shifting towards the securitisation of BIMSTEC, and this would subsequently be institutionalised. The 17th Ministerial Meeting, held in 2021, would recommend a restructuring of sectors and subsectors to streamline the functioning of the organisation, with the 5th BIMSTEC summit formally approving these recommendations the following year. Seven sectors emerged, including one exclusively dedicated to security, led by India and with three sub-sectors: Counter-Terrorism and Transnational Crime, Energy and Disaster Management.

The sub-sector that has since then been most active is on Counter Terrorism and Transnational Crime, which has subgroups on human trafficking, combating financing of terrorism, countering radicalisation, legal and law enforcement issues, and prevention of illicit trafficking. There have also been a number of diverse expert groups focusing on cyber security, maritime cooperation, space security and Himalayan science. Perhaps the most influential initiative under this were the meetings of the National Security Chiefs conducted in 2017, 2018, 2019 and, after a hiatus, again most recently in July 2024, hosted by Myanmar.

Table 1: Key initiatives on BIMSTEC security cooperation

There has been an equal emphasis placed on non-traditional security areas like disaster management and energy. There is even a separate sector for agriculture and food security. Under the Disaster Management sub-sector, two joint exercises have been organised since 2018, which consisted of tabletop exercises, field training and information sharing. The BIMSTEC Centre for Weather and Climate, assisted by a Scientific Advisory Committee, has also engaged in disaster management cooperation. The Centre’s governing board met thrice between 2018 and 2023 to effectively oversee its functioning.

With pressing challenges from climate and the need to secure natural resources for growing economic demands, BIMSTEC has also deepened energy cooperation from a strategic and security perspective.

With pressing challenges from climate and the need to secure natural resources for growing economic demands, BIMSTEC has also deepened energy cooperation from a strategic and security perspective. The Energy sub-sector has focused on grid interconnection, overseen by the Grid Interconnection Coordination Committee, following a Memorandum of Understanding in 2018. In 2022, the Energy Ministers of BIMSTEC countries met after a 12 year long hiatus. The newly established Energy Centre based in Bengaluru defines energy trade in the region for “enhancing energy security” as one of its key functions.

Finally, the securitisation of BIMSTEC also found expression in more regular engagements beyond the official, governmental or military tracks. Starting in 2017, BIMSTEC hosted or supported a variety of track 1.5 and track 2 policy dialogues that involved think tanks and experts from across the Bay of Bengal region. These platforms emerged as an important auxiliary site for informal exchange of perspectives on the regional security environment. Among the most frequent topics were counter-terrorism, cyber and maritime security (see Table 2).

Slow Progress and Different Conceptions of Security

The fast emergence of security as an area of cooperation from BIMSTEC member states poses some significant challenges. In terms of finalising common legal instruments, the organisation has not been particularly efficient. The sub group on Legal and Law Enforcement issues oversees a number of security related conventions, having met nine times. Despite this, gaining consensus on a range of regional conventions has been a difficult process plagued by numerous delays.

The Convention on Cooperation in Combating International Terrorism, Transnational Organized Crime and Illicit Drug Trafficking (mainly calling for cooperation between law enforcement agencies) was signed back in 2009, but only came into force in 2021, having been ratified only by India and Bangladesh for a long time. Similarly, the Convention on the Transfer of Sentenced Persons and Convention on Extradition is still being drafted and negotiated.

In some areas, the security sector seems to have adopted excessively ambitious goals that were quickly abandoned or paused. For instance, the Expert Group on Space Security Cooperation has not held a single meeting, nor has the proposed Home Ministers’ Meeting ever taken place. The Expert Group on Cyber Security Cooperation has also only met once in 2022. The organisation thus needs to be more strategic about selecting and prioritising areas for security cooperation and member-states should also be more willing to abandon areas where there is limited scope or persistent challenges.

Operationally too there remains a lot to be desired in terms of the frequency and level of participation from member-states. Till date there has only been one multinational military field training exercise, where Thailand and Nepal were merely observers. Regular joint naval or counterinsurgency exercises will be essential to the future success of BIMSTEC’s security sector.

The Secretariat’s security division (headed by India) has no dedicated director, and as of 2024 has remained in the interim hands of the Bangladeshi director in charge of the Trade, Investment and Development division.

India, despite being the lead of the security sector, barely plays a substantive role in the secretariat. India’s involvement with the secretariat has remained severely lacking, despite the Secretary General currently being an Indian official. India has only had two directors as part of BIMSTEC, well below the time put in by directors from Bhutan. Between May 2020 to July 2022, there was no Indian director deputed to BIMSTEC, and this has again been the case since November 2022 up to mid-2024. Resultantly, the Secretariat’s security division (headed by India) has no dedicated director, and as of 2024 has remained in the interim hands of the Bangladeshi director in charge of the Trade, Investment and Development division. While political will from New Delhi is important, it will be difficult for India to sustain and expand levels of security cooperation without allocating a full-time director and other resources to the BIMSTEC Secretariat.

Hosting meetings more consistently is critical to build rapport and trust among officials, especially when it comes to security cooperation on matters of “high politics” such as intelligence sharing or counter-terrorism.

Most importantly, member states need to utilise the organisation for more frequent engagements. Hosting meetings more consistently is critical to build rapport and trust among officials, especially when it comes to security cooperation on matters of “high politics” such as intelligence sharing or counter-terrorism. Sustaining this is a challenge but the socialisation element is important. For instance, the annual ASEAN foreign ministers’ meetings under the political-security pillar have taken place 57 times, with no hiatus in recent years (even through the COVID pandemic). Yet in the case of BIMSTEC, no National Security Chiefs meeting was held between 2019 and 2024.

Finally, BIMSTEC will also have to harmonise different perceptions of security among its member states. This gap is indicated by the wide range of different representatives at the NSC (see Table 3). The participants at the four meetings held so far include a mix of civilian, military, intelligence, and police representatives.

Political Instability and Security

After 2016, BIMSTEC has gone through a rapid trend of securitisation, with a variety of organisational changes and new initiatives. For the former Bangladesh defence and security advisor, Tariq Ahmed Siddique, BIMSTEC’s growing focus on “cooperative security” strived to collectively identify and combat shared security risks in the Bay of Bengal. With the region facing a variety of both domestic and transnational security challenges, both tradition and non-traditional, the stakes for BIMSTEC are high: will it be able to emerge as a site for deliberations, consultations and coordination, and maybe even as a platform for cooperative action?

The ambitious agenda started in 2016, and largely driven by India, is facing some significant headwinds from within its member-states. In 2021, a military coup in Myanmar ended its democratic experiment and the country has, since then, seen a spiral of new conflicts and instability. In 2022, Sri Lanka witnessed a massive political uprising and a financial default that severely curtailed its historical ambition to shape the Bay of Bengal into a regional economic and security commons anchored in BIMSTEC. And in 2024, Bangladesh plunged into political turmoil, ending fifteen years of political and economic stability that facilitated regional security cooperation. This is on top of other persistent conflicts between member-states, including Bangladesh-Myanmar tensions regarding Rohingya refugees with the potential of derailing or delaying BIMSTEC initiatives.

Rather than just formal cooperation structures, the organisations may play an important role as a platform for informal consultation on domestic, bilateral and regional security flashpoints.

How will BIMSTEC be able to craft a productive cooperative in such a difficult regional context? The way ahead will be rocky and require continued political investment from member states in BIMSTEC. The India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral of July 2024, held at the side-lines of the BIMSTEC Foreign Ministers retreat, may be one among several possible solutions: rather than just formal cooperation structures, the organisations may play an important role as a platform for informal consultation on domestic, bilateral and regional security flashpoints. This would be an adaptation of the “ASEAN Way” on political and security issues in the Bay of Bengal region.

Find on this page

The Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) is an independent, public policy think tank with a mandate to conduct research and analysis on critical issues facing India and the world and help shape policies that advance sustainable growth and development.