Explaining Expectations

Editor's Note

This column first appeared in Business Standard on July 27, 2014. Like all products of the Brookings Institution India Center, this is intended to contribute to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues. The views are solely those of the author.

Contemporary monetary policy is based on two fundamental premises. One, when inflation is above an acceptable level because of demand-side pressures, policy has to work to contract demand to bring it down. Two, if inflationary expectations are high and/or if there is risk of them rising, policy has to work towards moderating and stabilising them at low levels.In conventional business-cycle scenarios, the two objectives are often aligned, as inflationary expectations closely follow actual inflation rates. But when this does not happen, that is, when growth declines and inflation and, particularly, inflationary expectations remain high, trade-offs have to be recognised and choices made.

These premises provide a set of criteria on which the effectiveness of monetary policy actions can be judged. Looking back over the past five years or so, the slowdown in growth suggests that contractionary monetary policy did its bit to easing demand pressures. There may, of course, have been other factors contributing to the slowdown as well. With some lag, wholesale inflation also showed responsiveness to tightening, particularly its manufacturing component. So far, so good, if one were going by standard business-cycle dynamics. But did the monetary stance have any impact on expectations?

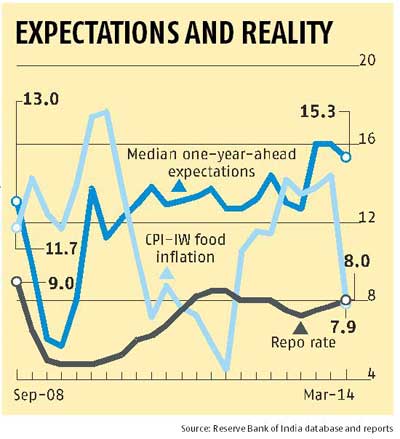

Not very much, if one were to go by the Reserve Bank of India’s quarterly household inflation expectations survey. The median expectation for the rate of inflation one year ahead is depicted in the graph. Expectations clearly dipped sharply during the 2008 financial crisis, but this was a period of strong monetary stimulus. They rose steeply as the crisis appeared to abate and then remained in the 12-14 per cent range for a long period, before rising further to the 14-16 per cent range over the last couple of quarters until March 2014. During th

is period, monetary policy was contractionary, going by the increase in the repo rate shown in the graph, except for the first three quarters of 2013, which coincided with the rise in expectations.

There are three possible interpretations of this pattern. One, the survey results are questionable. Two, monetary policy needed to be much more contractionary than it was to substantially moderate expectations. Three, there are factors other than monetary, which strongly influence expectations, and these have been particularly active during this period.

The first interpretation is tempting but risky to accept. However households may form expectations, if these translate into wage demands, they transmit into the overall price-formation process in theeconomy. There are, of course, other ways to gauge expectations, particularly the market prices of inflation-linked government securities. These were introduced last year. More on this later.

The second and third are mutually contradictory. If there are indeed forces shaping expectations that are outside the control of monetary policy, then a more aggressive policy stance might have slowed growth even further without having had an impact on expectations. Let’s assume for a moment that the third interpretation is valid. What might these forces be?

My bet would be on food prices, for a very simple reason. Expectations are very likely to be influenced by most recent memories. By far the most frequent and, consequently, recent transactional memory that most households have are with respect to food purchases. While this is true generally, the share of the typical household budget spent on food in India is likely to give this factor added significance. So can the persistence of high inflationary expectations despite the other business-cycle patterns playing out be attributed to food inflation?

The third variable displayed on the graph is food inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Indexfor Industrial Workers. It isn’t a straightforward story, but one could be told. In the early part of the period, the rapid acceleration in food inflation evidently ratcheted up expectations. However, when food inflation moderated after the initial surge, expectations, after some initial response, reverted to their previous levels; in fact, they started moving upwards. For more than a year, food inflation and inflationary expectations appeared to be de-linked. What might have happened?

We go back to the possibility of the monetary stance being too loose, but again, if this were the cause, the tightening during that period should have shown up in expectations moving down. Another possibility is the role of energy prices. In support of this hypothesis is the brief episode during the crisis, which is the only instance of a significant downward movement in expectations, coinciding with a massive drop in crude oil prices. After this, food prices appear to have taken over. But the sharp rise in oil prices in late 2010 and the months following may have offset the impact of moderating food inflation. In any event, this moderation reversed sharply in mid-2012, by which time oil prices had more or less stabilised.

In the more recent period, the pressure from food inflation may have been responsible for the surge in expectations. The fact that it coincided with a reversal in the interest-rate cycle may indicate that the monetary stance mattered as well. But, looking ahead, if this overall story is plausible, the decline in food inflation, stable oil prices and a steady monetary stance should signal a moderation in expectations in the coming months.

Those conditions are, of course, not guaranteed. Oil prices are vulnerable to conditions in Iraq and the broader West Asian region, though the impact so far has not been felt. Food inflation has been moderating, but the monsoon, notwithstanding the recent recovery, is still a threat to food production and prices. Both these factors constrain a change in the monetary stance.

Given that we cannot bring down oil prices, as long as they remain stable, the only conceivable way of bringing down expectations is a sustained decline in food inflation in combination with a clear monetary commitment to controlling inflation. Several components of a strategy have been articulated by the government; a comprehensive strategy needs to be articulated quickly.

Let me end by coming back to alternative gauges of inflationary expectations. An efficient market in inflation-linked bonds is a very important complement to household surveys. India has these bonds now, but various restrictions on investment and trade will prevent an efficient market from emerging. The slow progress in developing bond markets, of which this is one, denies policymakers a useful second window on to inflationary expectations.

Find on this page

The Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) is an independent, public policy think tank with a mandate to conduct research and analysis on critical issues facing India and the world and help shape policies that advance sustainable growth and development.